In Seymour Sarason’s 1970s book, The Culture of the School and the Problem of Change (pp. 105-106), he noted:

- Teachers ask between 45-120 questions per half-hour.

2. The same teachers estimate that they ask between 12-20 questions per half-hour.

3. Between 67 to 95% of all teacher questions require straight recall from the student.

4. Every half an hour two questions are typically asked by children in the class.

5. The greater the tendency for a teacher to ask straight recall questions, the fewer the questions initiated by children.

6. The more a teacher asks personally relevant questions, the more questions students ask in class.

7. These results do not vary across IQ level or social class.

Yet Scientist Isidor Isaac Rabi claims that his mother made him a scientist without ever intending to. When every other Jewish mother in Brooklyn would ask her child after school: “So? Did you learn anything today?” His mother would ask, “Izzy, did you ask a good question today?” Asking good questions made him become a scientist.

Fast-forward to today and in Ewan McIntosh’s TED talk he speaks about developing problem finders rather than problem-solvers, and now Project Zero’s Ron Ritchhart asks, “What if the culture of the classroom was question-centred?”

The Question Formulation Technique

Inviting questions in class is not the same as intentionally teaching the skill of designing good questions. The Question Formulation Technique offers a considered way to help students foster this essential learning skill. Teaching question design can help successful students to go deeper in their thinking and encourage struggling students to develop new enthusiasm for learning.

I usually introduce the Question Formulation Technique in one of the first lessons of the year. By introducing it early, I’m trying to make a statement that questions are more important than answers in my class and that it is OK to ask questions that we might not know the answers to. It is about fostering the disposition of curiosity and acknowledging that different people bring different questions to the table.

The second step is to improve the questions. Instead of open and closed questions, I find it helpful to talk about fat and skinny questions, kids get this, and I always pause here to have a classroom discussion about what a good question looks like and what is involved in producing a good question. I’m continually amazed at their depth of thinking and insights.

The third step is to prioritise the questions. I get them to choose the best two questions on their tables of four students, but before I do this I ask them to stop and consider the process of working together – ensuring that everyone contributes and nobody dominates.

Finally I get them to graffiti their best questions on the windows using liquid chalk. They love the sense of anti-authoritarianism in this. We then step back and look at their questions and talk about each of them.

Over the course of the coming term we try to answer each of the questions in some depth. Our students’ questions have much to teach us, and through the QFT process we have set a platform that we can keep looping back to as the year unfolds.

From Ping-Pong to Basketball Questions

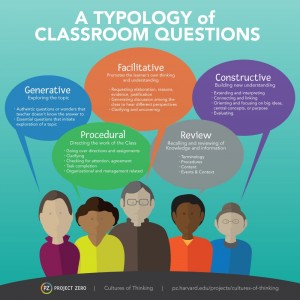

Questions are one of the prime ways teachers interact with students in classrooms. The ability to design an unGoogleable, engaging, open-ended driving question for a project-based learning unit is rapidly becoming a core skill for teachers. Ron Ritchhart claims that, “Our questioning helps to define our classrooms, to give it its feel and energy – or lack thereof. Questions are culture-builders, linking students, teachers and content together.” (Ritchhart, 2015, p. 221) As teachers, we all want to ask good questions, the kind that can drive learning and elicit deep thinking. Ron Ritchhart identifies five main types of questions teachers ask.

(Image credit: Project Zero)

When teachers start to focus on developing a culture of thinking, their questioning tends to swing away from procedural and review questions towards facilitative questions that push student thinking and make thinking visible. Taking his lead from Dylan Wiliam, Ewan McIntosh pleads with teachers to stop ping-pong questioning and try basketball questioning instead: “Pose a question, pause, ask another kid to evaluate the answer child one gave, and ask a third for an explanation of how and why that’s right or wrong.” Ritchhart also supports the basketball approach, “It begins to feel more like a basketball game in which we have lots of players taking turns with the ball, rather than a simple back-and-forth with the teacher.” (Ritchhart, 2015, p. 104) and “the ball (question) is passed around and ideas are bounced off one another, as the ball is moved down the court.” (Ritchhart, 2015, p. 213)

From Pop-corning to Ice-creaming

Project Zero’s Daniel Wilson (class, 2010), studied group learning in adventure racing teams for his doctoral thesis and he found that the most successful teams were far more likely to use conditional language when they were lost than the teams that were not so successful. “We might be here” rather than “This is where we are.” Teams that use conditional language are better at pulling together, pooling ideas, and harnessing group knowledge. In contrast, when absolute language is used, it seems defensive and assertive. When teachers use conditional language, students quickly catch on that they are looking for collective meaning-making and building on others’ thinking, rather than trying to guess correct answers. Wilson’s research also found that the successful teams that were using conditional language were more likely to ask each other questions and more likely to build on each other’s ideas.

Discussing this with classes can have a dramatic impact on the way that they talk and learn as a group. Several years ago one of my classes developed the metaphor of building on each other’s ideas like ice-cream scoops, instead of pop-corning their own individual thoughts. They even went as far as self-assessing themselves at the end of a class, “We did too much pop-corning today and not enough ice-creaming.”

Finally, it must be pointed out, that question-centred classrooms are unlikely to eventuate for students until we have more question-centred professional learning for educators. Coaching models, collaborative inquiry groups, action inquiry projects, and instructional rounds are the future of adult learning in schools.

Having a question-centered classroom will help my students to become more engaged in the lessons and make them want to learn new things that interest them. I will be finding a way to incorporate this into my classroom.

Using questions in the classroom is always a great formative assessment for our educators. When we involve our students with questions, we are checking for comprehension and understanding of the lesson. We need to make sure that the questions we are asking facilitate critical thinking and help our students think more on their own. We can engage our students by asking these types of questions. When our students are engaged in a fun learning environment, they are learning more! The attention is on the lesson each time. I really enjoyed this blog and will be making efforts to think about this topic more often when teaching in the classroom.

What I gained from this blog post was that, we as teachers can think we are asking our students the right type of questions because we simply ARE asking them questions. When in reality, they are still not gaining the experience of asking their peers questions and creating knowledge together. I really liked the ping-pong to basketball metaphor. That really helped me to understand that I have not created a completely student centered classroom.

I really like the analogue of basketball instead of ping pong which is what we tend to do. Thanks